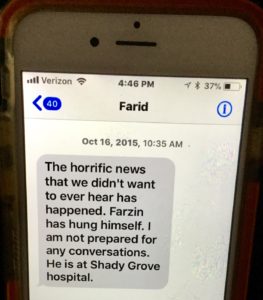

It was two years ago today that my brother-in-law, Farid, sent me a text message that my husband had hanged himself. He had already reached my sister and told her the news upon which she immediately responded by telling my brother-in-law that I was at school teaching, it was my first day on the job, and she would go get me. She asked him not to send any messages, she would give me the news. But he was eager to let me know of my beloved’s action and in the same message tell me he was in no condition to talk, meaning to me.

The text was sent approximately an hour after Farzin hanged himself. Farzin had called his brother several times that morning before he hanged himself.

I had a room full of children and I went blank upon reading the text message. I had talked to Farzin about 7:00 am that day and I did not detect anything suspicious in his voice; he assured me he would be home for the weekend. I sat down and stared at the message. At one point I assured myself he must be alive, he’s at a hospital. Within minutes my sister was at the door with a school administrator. She put her arms around me and pushed me out of the room and into the car. I barely remember what we said to each other. What I know is that her presence kept me breathing.

The drive to Shady Grove Hospital took several hours. No one from Farzin’s family called me. When I entered ICU, I went straight to Farzin’s room, where his brother Farid was pacing. The remaining family of sisters, a cousin and nephews were sitting in the waiting area. The ostracism by my husband’s family, with whom I had shared a close and loving relationship for over 20 years, had started about a year before Farzin took his life. They blamed me for not taking good enough care of him. Of course the issues were broader; the type of care Farzin should have or not have, hospitalizations, medicines he was on, his doctor of 20 plus years and everything that they were confronted with upon directly facing the full dimensions of Farzin’s mental illness.

Farzin was on life support. The doctor calmly told me Farzin was brain dead. I know what brain dead means but I had no idea what to do with the news or how to apply it to my Farzin. My questions were simple ones; how do you know, is he in pain, can he hear me? A long explanation followed my first question. The doctor pointed at the severe ligature marks and tears around his neck and attempted to explain that Farzin had experienced a lack of oxygen flow to the brain for a significant period of time. No he can’t hear you, I was told. Really? How do you know, I thought.

The doctor walked over to Farzin’s bedside and with one hand opened each eyelid and shined the light directly into his eyes. As you can see she told me, there is no eye movement and a complete lack of pupillary response. But I saw something different, beautiful brown eyes heavily lashed. The brown was a deep cavernous brown, that had swallowed me on many occasions. No, he doesn’t look dead to me I thought.

Is he in pain I kept asking. We really don’t know the answer to that, two doctors informed me. Probably not, one replied. But he could be, I responded, and I don’t want him experiencing any pain at all. He has experienced enough in his lifetime. They offered morphine but with too much hesitation for me to accept. I want Farzin to have it now, I insisted. .

And no I am not in agreement to take Farzin off the ventilator. The words were rushing out of me as quickly as I thought them. Nothing was real and everything I was told put me at odds with everyone and anyone who entered the room. There was hysteria erupting from me and I was at war with everyone. It was irrational and yet I felt no one understood anything.

Much later that night my sister and I went to a hotel a short distance away and returned early the next morning.

Oh Gigi how horrific, I think expressing your feelings here ,especially about you’re Farzin”s death is really good for you ! You do whatever you need to do to get through this…….. love

My heart goes out to you. Losing a beloved husband is anguish. Losing him in this way…beyond words. Thank you for sharing your grief. It is my deep hope that you are aware that you are loved.

That text was a group text for all the family members of Washington area. Farzin, had called me once that morning and I rushed to the apartment as fast as I could (as I had done the previous two attempts that he had in Gaithersburg by over dose,….). Once I got there and I saw that HORRIFIC seen, I was frozen. After calling 911, I felt my responsibility to let the family members know, as awful as news that it was. There is not a day or night that passes by without me having that nightmare seen in front of my eyes. It is an excruciating pain to deal with and the event has caused what seems to be unrepairable tears to the family.